Hi Everyone,

I find paradoxes very interesting because they are counterintuitive. Paradoxes can be useful in helping us understand each other and our environment. In this post, I am focusing on paradoxes that may give us more when we strive for less. I am not delving into detail on any particular paradox but instead emphasizing some consistent themes with these paradoxes. I have also included several diagrams to demonstrate relationships between desired outcomes and likely outcomes if something is over pursued.

Paradox of tolerance

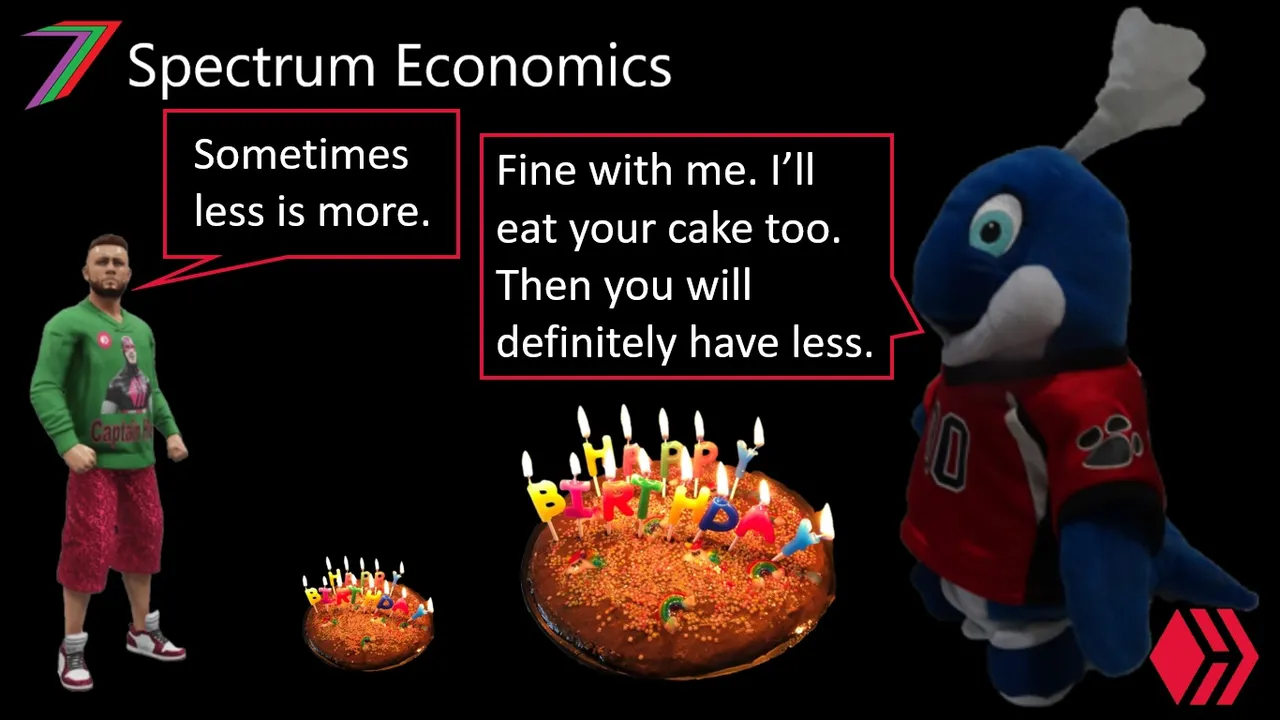

In my recent post, A World of Tolerance, I briefly discussed the idea of a paradox of tolerance. If people were completely tolerant of all behaviour, society would become more intolerant rather than more tolerant. This is because we would be tolerant of intolerant behaviour. Therefore, intolerance would be allowed to flourish. Figure 1 contains a diagrammatic example.

Figure 1: Example of Paradox of Tolerance

Where: OT is optimal tolerance and TT is total tolerance.

In Figure 1, there are two curves. The yellow curve represents a society with people who are less tolerant. The green curve represents a society with people who are more tolerant. For both societies, there is an optimal level of tolerance. The peaks of the curves represent the optimal level. The peak of the yellow curve occurs sooner and at a lower level of tolerance than the green curve. This indicates that we can be more tolerant in a society with more tolerant people. In a society with many intolerant people, we will not be able to be as tolerant. However, through selective tolerance. It should be possible for a society represented by the yellow curve to move towards the society represented by the green curve.

Paradox of generosity

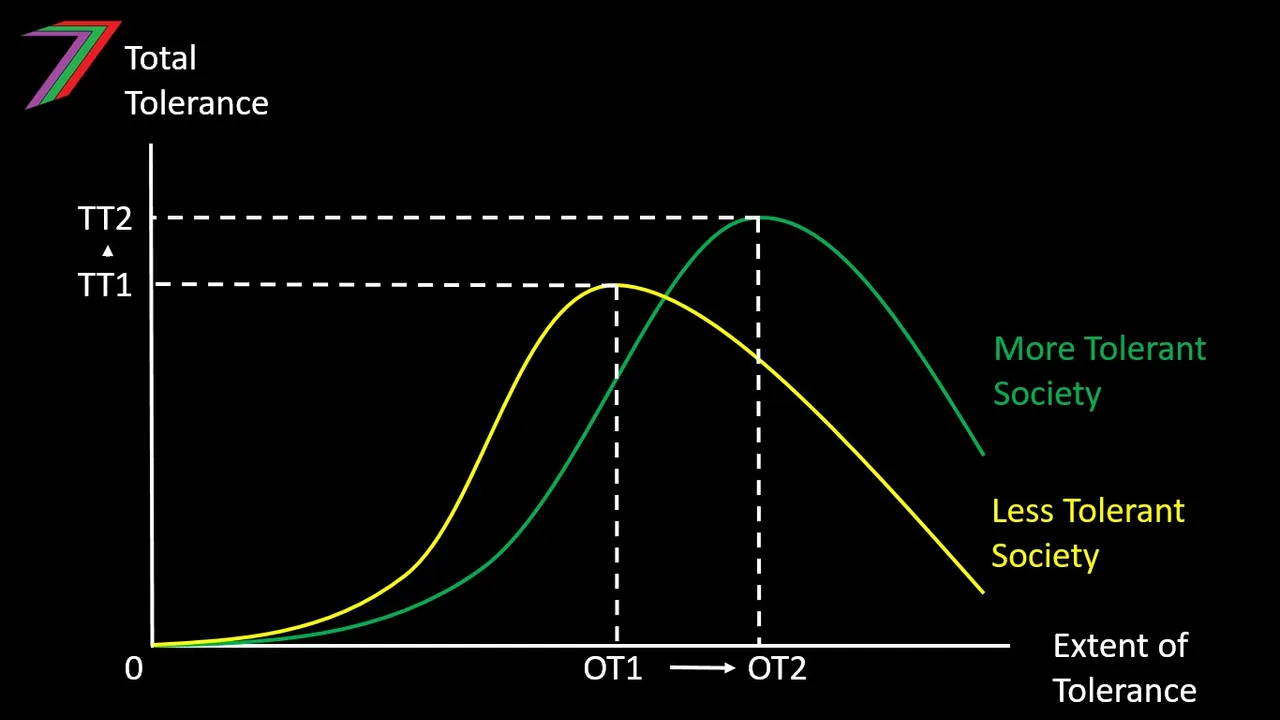

We could also argue that there is a paradox to generosity. Generosity can breed generosity but arguably only to certain extent. People often repay generosity with generosity but that does not universally occur. Some people will exploit the generosity of others and not offer anything in return or to anyone else. Figure 2 contains a diagrammatic example.

Figure 2: Example of Paradox of Generosity

Where: OG is optimal generosity and TG is total generosity.

Figure 2 is very similar to Figure 1. In a generous society, it is easier to be generous to more people, as generosity is more likely to be received in return. In a less generous society, offering generosity is more difficult if it is rarely offered in return. In an ungenerous society, the offering of generosity will need to be more selective. The amount of generosity offered to the ungenerous should be reduced. Therefore, lack of reciprocity of generous behaviour is punished with reduced future generosity. It should also be important to distinguish between ungenerous behaviour and a lack of ability to be generous. Some people may not necessarily be able to offer as much generosity based on their circumstances.

Paradox of freedom

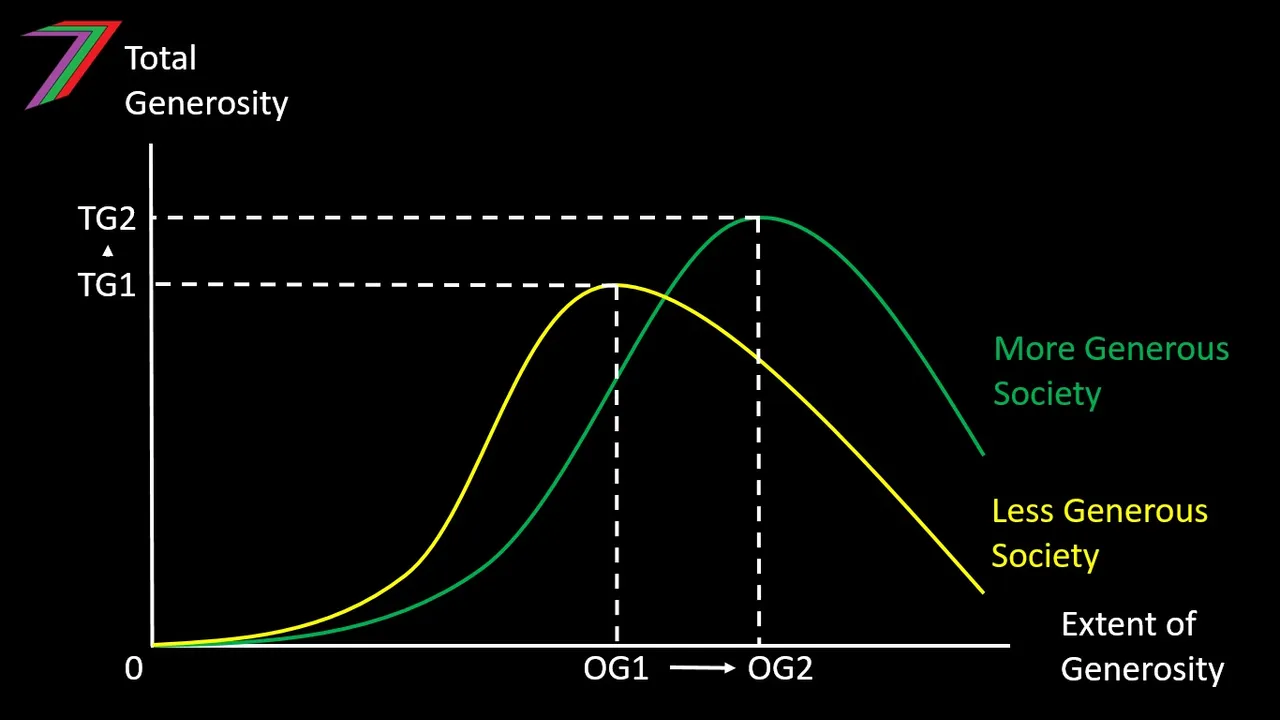

There is also a paradox of freedom. Increased individual freedom may not always lead to increased freedom for all of society. If everyone were given complete freedom, some people would use their freedom to oppress the freedom of others. Figure 3 contains a diagrammatic example.

Figure 3: Example of Paradox of Freedom

Where: OF is optimal freedom, RF is reduced freedom, and TF is total freedom.

In Figure 3, there are two curves. The yellow curve represents a society with a structure of governance. As the curve moves to the right, the strictness of governance is reduced until it reaches zero. The peak of the curve, greatest amount of freedom for society, occurs before the strictness of governance is reduced to zero. Beyond the peak, people start to use their freedom to infringe the freedom of others. At some point, the people whose freedom is being infringed on will cooperate to obtain their freedom back. The red curve represents the affect such cooperation could have on freedom. The informal authority reduces the freedoms of all. The reduced individual freedom initially increases overall freedom but if the informal group becomes too powerful and too authoritarian, both individual freedom and overall freedom will fall.

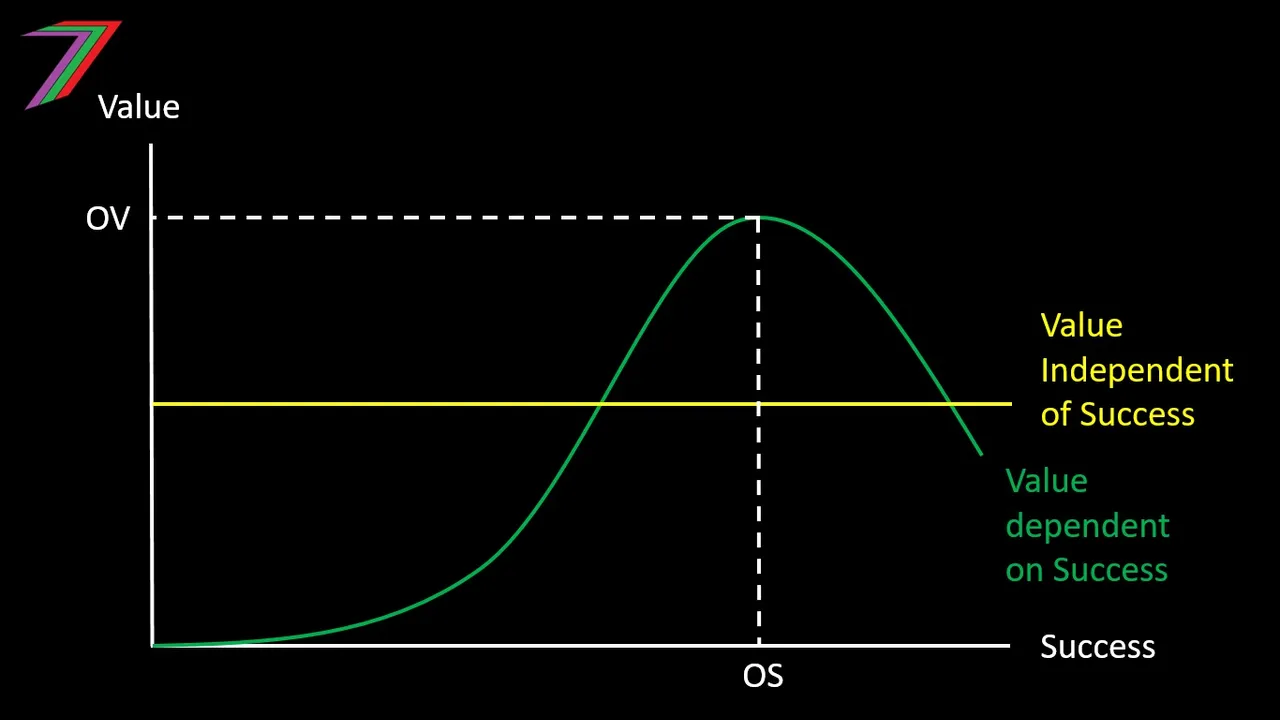

Paradox of success

In my post, How often do you want to succeed?, I discuss the importance of failure. Failure enables us to learn from our mistakes as well as appreciate our successes. Both of these create a paradox of success. Learning from our mistakes can enable us to achieve success that is more significant. Greater appreciate of success will make success more valuable. Without failure, success is likely to be taken for granted and therefore loses value. Figure 4 contains two examples of how a paradox of success could occur.

Figure 4: Paradox of Success

Where: OS is optimal success and OV is optimal value.

In Figure 4, there are two curves. The yellow curve represents a person whose total value obtained from success is independent to the occurrence of success. For example, this person obtains the same value from succeeding 1 out of 10 times as succeeding 10 out of 10 times. The value of the one success is ten times more valuable than each success if the person succeeds all ten times. This is because success has become rare and therefore more valuable.

The green curve represents a person whose total value obtained from success is dependent on the occurrence of success. For this person, each success brings value to the person but at diminishing rate, as success becomes less rare. Eventually, success becomes so frequent the value of new successes, as well as previous successes, begins to fall. Success begins to be taken for granted. This point occurs at the peak of the curve. After this point, there is a paradox of success. This person needs to fail to continue to enjoy being successful.

Paradox of happiness

There are several possible versions of a paradox of happiness. One version involves a paradox of the pursuit of happiness. Happiness cannot be obtained through direct pursuit but instead it can be obtained through the pursuit of what provides happiness. This involves understanding what truly provides happiness.

Another version of the paradox of happiness relates to the normalising of what provides us with happiness. We may pursue what we believe makes us happy. We may obtain what we believe makes us happy. This may actually provide us with happiness. However, we may continue to pursue more things that we believe will make us happy. Therefore, we could forever find ourselves pursuing more things that we believe will make us happy rather than enjoying what we have already obtained.

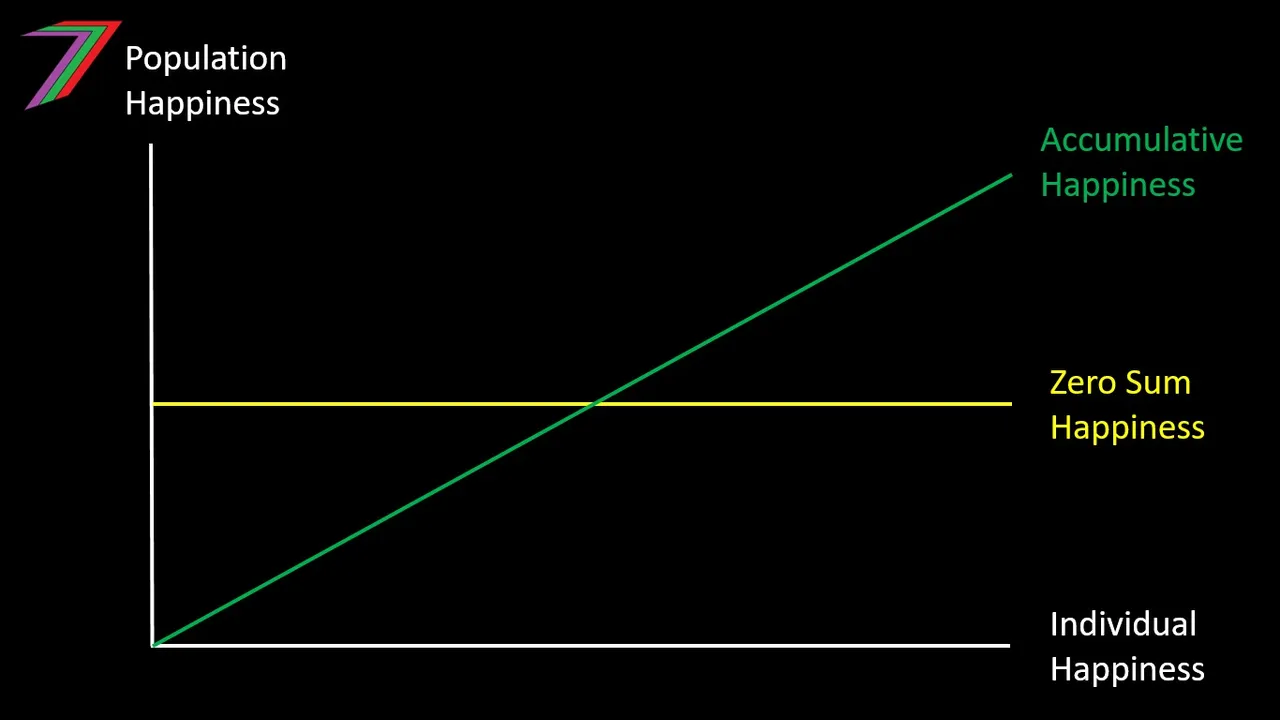

The third version of the paradox of happiness relates to our happiness in regards to other people. Happiness of individuals and society can grow together. As each person becomes happier, so does society as whole. However, this is not always the case. The overall happiness of society may not be affected by the increase in the happiness of one person. An increase in happiness of one person could lead to a decrease in happiness of other people. For example, a family might be happy with their car until they find out that the neighbours have a much nicer car. The neighbour’s happiness has increased because they have a new car but the happiness of the family that does not have the new car decreases. This paradox is described in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Example Paradox of Happiness (Version 3)

Figure 5 contains two curves. The green curve demonstrates a constant positive direct relationship between an individual’s happiness and the happiness of society. The yellow curve demonstrates a zero sum relationship between an individual’s happiness and the happiness of their society. As an individual’s happiness increases, the happiness of society falls by an equivalent amount. Reality is likely to fall somewhere between the two curves. Some individual gains in happiness will positively affect society while others may negatively affect society. This will vary depending on how individual people obtain happiness and the culture of the society.

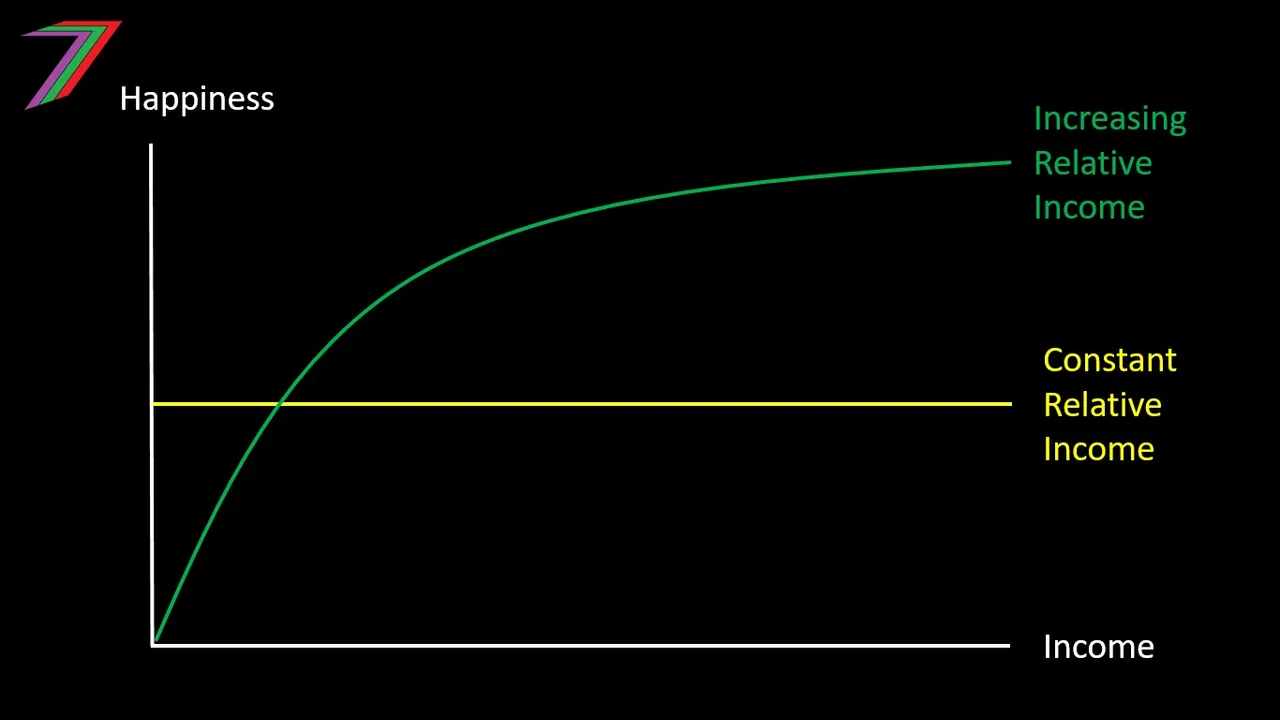

Easterlin Paradox

The Easterlin Paradox is an extension of the third version of happiness explained in the previous section. Easterlin Paradox relates to the relationship between higher income or wealth and happiness. Initially, there is a positive direct relationship between income and happiness. However, this does not hold true in the long-run. Richard Easterlin has highlighted throughout his collection of works that the overall happiness of populations has not increased over time despite increasing income and wealth. The likely cause of the short-run increase in happiness is because the increase in income or wealth is relative to the rest of the population. In the long-run, income and wealth increases for the entire population.

Figure 6: Easterlin Paradox (short-run vs. long-run or relative vs. absolute)

Figure 6 shows, using the green curve, that as a person's relative income increases so does their happiness. However, the rate of increase in happiness diminishes as income and wealth increases. I describe the relationship between happiness and wealth in my post Relative Utility Approach. In this case, the Easterlin Paradox does not apply. The yellow curve shows no change in relative income even though income is increasing. The yellow curve represents the long-run relationship between income and happiness described by Easterlin.

Another Income-Happiness Paradox

We can also consider the relationship between income and happiness based on what we require to sacrifice to obtain happiness. Earning income typically requires the sacrifice of time. The enjoyment of what can be acquired with a higher income also requires time. To obtain happiness we need both income and time. If we assume a fixed hourly wage rate, obtaining more income leaves less time to enjoy what that income provides. I describe this relationship in some detail in my post Quality of Life as Quality of Time. Figure 7, diagrammatically displays this relationship.

Figure 7: Relationship between happiness and work-based Income

Where: OI is optimal income and OH is optimal happiness.

The relationship between happiness and income is also implied by the backward bending demand curve for labour. As income increases, people are willing to work more hours. However, after a particular hourly rate is reached, people are less willing to work more hours. This is because additional income holds less value than the freedom they can obtain by working less hours. I explain the backward bending curve in my post Quality of Life as Quality of Time.

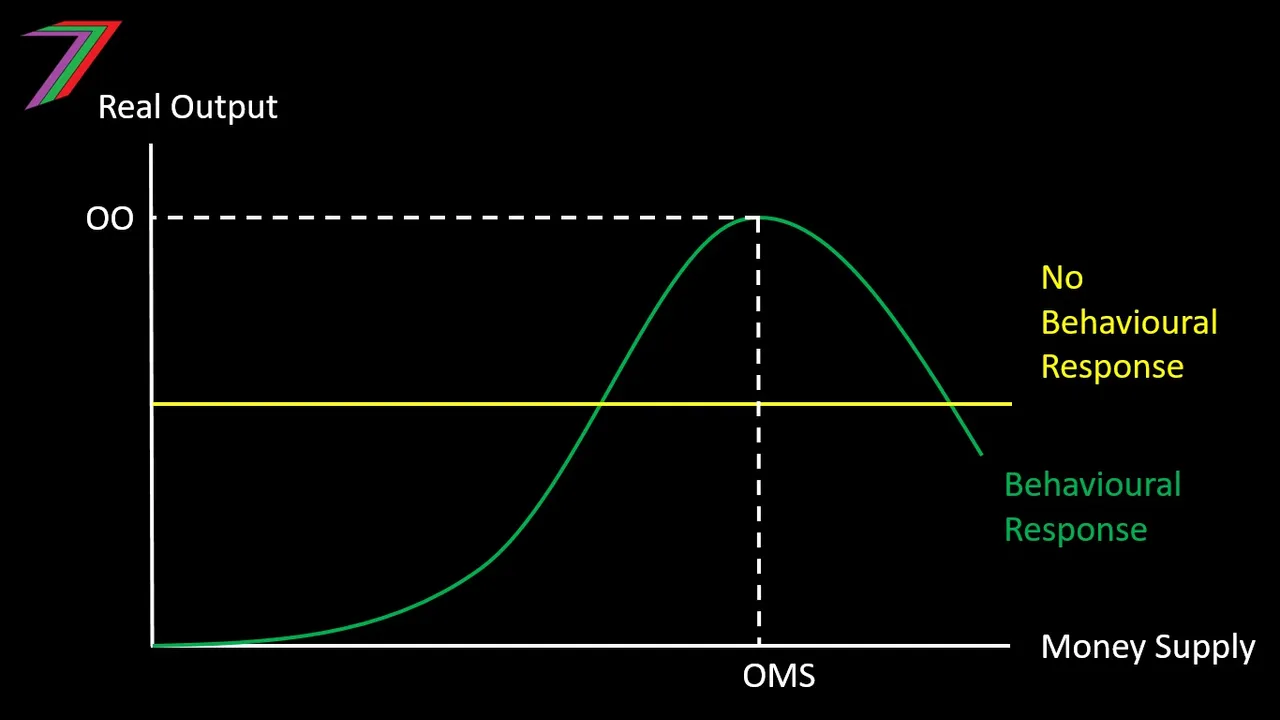

Paradox of money

We could argue that there is a paradox of money. This paradox relates to the relationship between supply of money and real income (i.e. Money Supply × Velocity of Money/Price Level = Real Income). Real income relates to real output. The physical supply of money is not determined by real output; it is determined by Government and/or the banks based on their criteria for money creation. However, increasing money supply can stimulate investment and consumption, which can raise the level of output, which increases income. Figure 8 describes possible relationships between money supply and income.

Figure 8: Money Supply and Output

Where: OMS is optimal money supply/optimal increase in money supply and OO is optimal real output.

In Figure 8, the green curve represents an economy where there is a behavioural response (i.e. investment or consumption increase) to an increase in money supply. An excessive increase in money supply would also be detrimental, as the currency would be become inflationary (i.e. losses value), which would cause a reduction in investment. The yellow curve represents an economy, which is indifferent to money supply. This is logical if increasing money supply causes no behavioural response, as increasing money supply does not directly represent increasing output. Both these scenarios represent a possible paradox. I would argue this an illusion of a paradox but still worth discussing because of its application in the real world.

What can we learn from similarities between these paradoxes?

In this post, I have discussed several different paradoxes where, under certain circumstances, striving for less can lead to more. A key similarity between these paradoxes is that they do not occur immediately. They occur beyond a particular point. Therefore, we can strive for an optimal level of something, which is not necessarily the maximum level. The optimal level may not be difficult to identify. In the case of tolerance, freedom and generosity, they can be targeted. For areas such as success and happiness, we need to be able to identify what gives us value. For example, some people might be consistently successful because they only focus on areas where they are guaranteed to succeed. This is unlikely to be very rewarding. Attempting to do something where there is a higher chance of failure might be more meaningful. However, there needs to be at least some chance of success as continuous failure is also not rewarding.

These paradoxes also highlight how relationships can be complicated as well as integrated. Often, what affects us also affects others either directly or indirectly. A paradox often occurs when whatever benefits us, indirectly harms someone else. For example, if we use what we have gained as a gesture of superiority. Instead of an attitude of ‘I-am-better-than-you’, we could have an attitude of ‘we-can-make-each-other-better’. We can move from an attitude of competition to an attitude of cooperation. In many cases, zero sum games do not need to exist.

Conclusion

In this post, I have discussed paradoxes relating to tolerance, generosity, freedom, success, happiness, money and wealth. These paradoxes have several things in common. Each paradox may lead to an outcome that does not involve maximising the input most associated with that output. This is counterintuitive. This post has provided possible explanations to why these paradoxes occur as well as explained a few commonalities between these paradoxes.

I believe understanding paradoxes is a useful exercise. An eventual paradoxical relationship is sometimes unavoidable. Therefore, we need to understand when these paradoxes occur and how we can avoid their potentially negative effects. Paradoxes can also provide a warning if we are unnecessarily limiting others or even ourselves. Paradoxical relationships caused by unnecessary competition do not need to occur. Instead, we can work together so as achieve a better outcome for all involved.

More posts

If you want to read any of my other posts, you can click on the links below. These links will lead you to posts containing my collection of works. These 'Collection of Works' posts have been updated to contain links to the Hive versions of my posts.

My New CBA Udemy Course

The course contains over 10 hours of video, over 60 downloadable resources, over 40 multiple-choice questions, 2 sample case studies, 1 practice CBA, life time access and a certificate on completion. The course is priced at the Tier 1 price of £20. I believe it is frequently available at half-price.

Future of Social Media