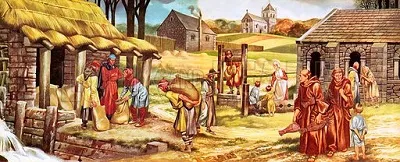

"Work, justice and religion on a mediaeval English village by Ron Embleton"

image source

The era of the Middle Ages between the thirteenth and the sixteenth century A.D. was a time when the Church was still working to superimpose its beliefs and monotheistic structure on rural society across Europe. The main points of resistance to a smooth changeover were that firstly, the villagers had been using techniques to aid their everyday living which had been passed down to them from many generations before and were seen to be working to keep their lives orderly; secondly, being practical people utilising any and all tools available to them, the villagers had begun to blend both the traditional with the newer ecclesiastical information, as perhaps a way of ‘hedging their bets’ or ‘covering all bases’ and they saw the two worlds complimenting each other well; and thirdly, it was not only resistance by the lay villagers the Church had to contend with, but with many of their own village clerics, who not only utilised the blending of the two practices to aid their villagers’ everyday lives, it was very likely that they did not differentiate between – or defined differently – what was ‘religious’ and what was ‘pagan or magical’ and being under so-called demonic influence. To them, it was probable that many of the simple everyday charms and rituals were ‘harmless’ and in fact used to invoke God’s good will, and they may not have often struck an incident which was of far more malicious intent and pointing to demonic interference. Whether a ritual, charm, celebration, shrine or other means by which a rural village member – or group of members – was either based on or intended to be some form of pagan, magic, superstitious or religious work in all likelihood simply came down to a matter of perception and expediency, by both the user and the judger.

"Pagan feasts depicted on an illumination from the Rus chronicle

image source

According to modern sources like the Oxford dictionary, the definition of ‘pagan’ is ‘a person who holds religious beliefs that are not part of any of the world’s main religions’;2 the definition of ‘magic’ is ‘the power of apparently influencing events by using mysterious or supernatural forces’;3 and ‘superstition’ is defined as ‘a widely held but irrational belief in supernatural influences, especially as leading to good or bad luck, or a practice based on such a belief’.4 It is possible that for any non-Christian, the very definitions of magic and superstition could very well be applied to Christian beliefs and practices, and they could even legitimately view the Christian religion as being pagan when compared to their own beliefs. The Christian belief in God could be viewed as an intangible, mysterious, supernatural influence who is called upon to bring luck in some form to the believer. The Christian Church developed its own set of religious rituals which could be viewed as being based on magical, superstitious, or supernatural ideas, although, in the Christian’s view apparently ‘pagans worked magic, but Christ worked miracles’5 and even if, for example, something that an apostle did appeared to be a work of magic, it was instead ‘God’s power working through them’6 and therefore perfectly acceptable. Contemporary definitions of ‘superstition’ ran along thoughts that ‘superstitions were “observances” which had survived from another age, and for which they were a kind of evidence’,7 so probably viewed more like folklore.

necromancy - "An astrologer looking at the sky with a demon inside a circle (London, British Library, MS Royal 6 E VI, f. 396v, London, c. 1360-1375)."

image source

Contemporary – and earlier – Middle Age’s possible definitions of the word ‘pagan’ place the general meaning as referring to one who is heathen, unclean, peasant, idolater, or a ‘rural celebrant of non-Christian religious festivities’;8 obviously all such labellers content to give the word a negative connotation. Superstition was a label often used by those who condemned it to imply ‘irrational and improper religious practice’.9 Thomas Aquinas defined it as divine worship ‘rendered in the wrong manner or to the wrong subject’.10 Defining the word ‘magic’ in contemporary terms was more difficult, but some time during the Middle Ages the word was given two main categories – ‘natural magic’ and ‘demonic magic’. The former referring to ‘the wondrous powers within nature’11 in its many varied forms, and the latter the more ‘supernatural’ or unaccountable forms, and under this heading may have been grouped rites practiced ‘for unacceptable ends, or by inappropriate persons, or with reprehensible techniques’;12 and possibly if a ritual, rite or other such practice was condoned by a clergyman it would likely not have even been viewed as having ‘magical’ connotations. ‘Magic’ had an intangible quality and would have been difficult to define in no uncertain terms, and so the reality of what would or would not have been labelled as ‘magical’ would have been subjective and therefore reliant on the perception of those using it, naming it, or disavowing its existence. An example of perceiving the same act quite differently was when three women in a late sixteenth-century rural area of France carried a sick infant into the village in order to enlist the aid of Saint Peter in curing the child. Basically they walked through a certain woman’s house while performing small rituals, on their way to the cemetery, from where they carried out further rituals while appealing to Saint Peter. Once the Protestant church got wind of what had happened they investigated the incident, calling it ‘a vile superstition and horrid idolatry’13 whereas when a late nineteenth-century Catholic vicar heard the story he thought ‘it offered stirring proof of the survival of medieval Catholic devotion to Saint Peter’14 while in a deeply Protestant community. Probably for the Catholic his perception was weighted up against his belief and an anti-Protestant feeling, and if the woman had carried out the ritual in a Catholic area she would likely have been condemned by the Church for her superstition similarly to what the Protestants did; so it was as much a political view as an ecclesiastical one influencing perceptions.

the parish priest

image source

‘Many aspects of the common magical tradition could be practiced by anyone … [y]et perhaps the most common such figure … was the local village priest. There is ample evidence that priests were widely regarded as ritual experts whose special knowledge and power extended well beyond the official ceremonies their position required them to perform.’15 It was believed that if a priest performed any ritual, blessing, charm, divination, spell, healing, or rite it became more powerful or effective, as he was the representative of God. Sometime during the early fifteenth century there was the case of an Augustinian friar – Werner of Friedberg – who was challenged by a university theologian – Nicholas Magni of Jauer – in his sanctioning of a common charm for healing used by the local villagers. Nicholas, and local authorities, were concerned that the charm: “Christ was born, Christ was lost, Christ was found again; may he bless these wounds, in the name of the father, son, and holy spirit.”16 could in actual fact draw on demonic power, rather than divine, by invoking ‘conscious intelligences’. There was no surviving conclusion to the outcome of this charge, but the case was likely indicative of a general concern by clerical authorities that there were elements of religious practice being wrongly used. In the words of the charm itself there is seemingly no link to demonic forces, rather the opposite, so one can only assume that it is more the fact that it was being used by lay people that was the real concern. Lay people had no religious training or induction into the Church, so therefore had no direct path to God and His protection, or understanding of His will; thereby being susceptible to the trickery of demonic forces, possibly even becoming an unknowing vessel for the Devil’s work. This incident occurred during a period where the Church was re-examining its concerns over magical practices and superstitions, and formulating a picture of organised group gatherings by satanic followers, based around magical practices and superstitions. Extrapolating layperson practices which were once accepted – if not approved of – by the Church and giving them an evil overtone was becoming common in fifteenth century Europe. Healing and love potion practices which had once been used by villagers with a charm or blessing invoking God’s protection, and often with the full knowledge of the local laity, were suddenly called into question by ecclesiastical theologians. Magical ritual ‘inhabited a twilight zone shading from a purely spiritual, ecclesiastically sanctioned notion of ritual efficacy through to an instrumental, magical view, not far removed from practices explicitly prohibited by the Church.’17 It was observed that ‘the pagan definition of magic had a moral and a theological dimension but was grounded in social concerns; the Christian definition had a moral and social dimension but was explicitly centred on theological concerns’18 and the two could not comfortably find any common ground to work with, and certainly there appeared to be many grey areas of practice, under dispute.

one of the Struell Wells - holy site, Downpatrick, Ireland - where the water was believed to have great healing properties

image source

While the Church condemned the practice of worshipping at shrines dedicated to nature – stones, trees, fountains – and places ‘where the ways on highroads forked or parted or crossed’.19 These places were usually used as a focal point for invoking supernatural forces in the aid of villagers’ everyday life, such as health & wellbeing, crop success, animal health, and specific or general protection. The Church saw these shrines as places where demonic forces dwelt or could slip through into the physical world and cause havoc. But the Church also had its own shrines, where the layperson could go and seek aid from particular saints. These shrines might consist of relics or body parts of the deceased saint, and often a small commercial venture emerged whereby a visitor seeking healing or spiritual cleansing might purchase a small ‘souvenir’, and it was often enterprising monks who were the vendors; ‘a successful shrine could mean big money for the religious foundation involved’.20 Churches were also known to place their buildings of worship over top of sacred pagan sites, in order to both absorb, integrate and dominate the spiritual value the villagers placed upon the sites. The ‘pagan’ shrines were ‘places central to the lives of their adherents when these felt the need for supernatural assistance’21 and as the Church perceived that ‘[r]eadily acceptable alternatives for such places and habits [were] never easily to be found’22 it was much simpler for them to take over the site and turn it into a place of religious worship, aid and guidance. It could perhaps be argued, then that in the case of shrines, the religious practice was a rather pagan act, and only its sanction by the Church changed its perception. During the late sixth century, Pope Gregory the Great ‘told his missionaries to England that they should not demolish pagan temples but reconsecrate them and use them as Christian churches; and that they should endow pagan festivals with Christian meaning rather than prohibiting their observances.23 Missionaries may have even gone so far as to turn pagan charms into Christian ones, as indicated by when: ‘a famous early German charm tells how Woden was riding a horse through the woods when its leg was sprained and the god had to heal the afflicted limb. Later versions replace Woden with Christ, portrayed as riding his horse into Jerusalem, or with other Christian figures.’24 Religious and non-religious practices constantly overlapped in the villagers’ lives as they went about their everyday business, with their use of both practices blended into charms, protection, healing, celebrations and sacraments, and likely never thought about defining the parts which made up their rituals. What was most important, for them, was the outcome, and as such ‘[t]he most basic purpose for magical rites, items, and spells was to heal’25 and healing was done not only by the village healer, midwife or barber-surgeon, but by monks at the monasteries in both a practical and spiritual role. Even the local clergy would have at the very least prayed over people for recovery from disease or accident. Good health was an important part of village life.

the priest with his fellow villagers

image source

‘At least up to the thirteenth century, rural priests seem to have been essentially grass-roots purveyors of ritual, happy to oblige their parishioners with uncritical use of such rites as they could perform.’26 Perhaps one of the difficulties of separation of pagan and Christian beliefs for the local clerics was that usually they had roots in the village they then worked in. They grew up surrounded by the ‘usual’ customs and rites which purportedly helped keep their villages safe from harm and ensured ongoing good harvests. To then turn around and have to – or even want to – deny those local customs to their fellow villagers must have been extremely difficult, especially as so many of the villagers believed that it was God who they were appealing to, not some so-called demonic forces. They also saw nothing ‘evil’ in divination and casting lots. ‘Just as God granted knowledge of future events by means of visions and transports vouchsafed to Daniel and John of Patmos, so it was thought that he continued to do so for saints such as Hildegard and Bridget and for specially chosen monks, hermits, and even laymen.’27 But, the Church in the Middle Ages frowned heavily on any form of divination – especially by a layperson, claiming it to be demonic forces at work through an unwary host, although ‘if the setting seemed right and the prophet worthy, the vision might be widely accepted’.28 So the distinction between ‘worthy’ and ‘unworthy’ from the viewpoint of the Church seems to have been more a matter of perception, convenience and lack of threat to their doctrine. If they perceived the host to be suitably ecclesiastical and it was convenient – or expedient – for them to claim divine sources which they could justify with their doctrine, then they were happy to do so, otherwise the event, object, or ritual could be relegated to the realms of ‘pagan’, ‘superstitious’ or ‘magical’ and therefore ‘demonic’; but ‘[c]lerics as well as laypeople, nobles as well as peasants, intellectuals as well as the uneducated all engaged in some way in these activities.’29 John of Gaddesden practiced an interesting mix of empirical, theological, worldly and folkloric training as a physician in the early fourteenth century, as an excerpt from his Rosa medinae showed:

[For a nosebleed] let us now consider an empirical approach: Go to a place where the sanguinaria (i.e., shepherd’s purse) grows and kneeling say Our Father and Hail Mary, etc. Then [say] this versicle: “You, who have redeemed us by your Precious Blood, we ask you to come to the aid of your servants.” And then collect one or two plants. But if you collect more plants, it would be fitting to repeat these prayers. And then hang this plant about the neck of the patient from whom the blood flows, and instantly it will stop and surely constrict.30

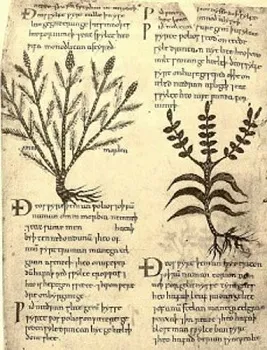

the Anglo-Saxon Nine Herb Charm

image source

The charm seems to have been an interesting blend of superstition, religion and herbal folklore. His theories and practices must have been acceptable to at least some of his peers as he was physician in the English court to King Edward II. For the charm to be seen as pagan one would only have to remove the words ‘Our Father and Hail Mary’ or replace them with names of gods or deities, leaving all other instructions intact. It would take very little to change perceptions. Evidence of another such blend of religious and folkloric – or superstitious – belief and practice comes from the commonplace book of Robert Reynes, a yeoman, churchwarden and likely reeve in Acle, Norfolk, England during the late fifteenth century. From his many entries one can discern glimpses of everyday life for this working villager, which included charms, methods of divination, prayers, sacraments, religious feast days and notes on the zodiac. He would have been concerned not only with animal fertility, crop success, good weather and villagers’ health, but with the organisation and running of religious events and villagers’ spiritual well-being. Many of the more religious and superstitious entries could have easily been viewed by the Church as magical or pagan and therefore demonic. The entries in Reynes’ book show that he was a learned man, with civic responsibilities, and must have had at least some conversations with the local clergy, so it is likely that the clergy either did not disapprove of the more superstitious of the practices, found they could not override the long-held practices of the villagers and learned to turn a blind eye to them, or possibly knew that it would take many long years to wipe out these practices until they were no longer used or remembered, and slowly overlaid the superstitious practices with those of religious ones.

Remember us, O Lord, so that, just as you promised our fathers Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, you spare your wrath from our borders and fields, and defend our crops so that they may come into your church freed from infestations by their enemies, and may be stored away in our barns so that wayfarers and the poor refreshed by them together with us may bless the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, who live in perfect trinity … 31

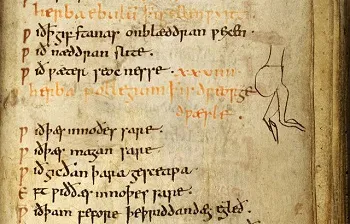

a midwifery page from the book Pseudo-Apuleius

image source

It seemed quite common for the villagers to believe that what they were doing was utilising a belief in God in their everyday practices, and not have separated them into categories of ‘magic’ or ‘superstition’ or ‘pagan’; and probably more so in the rural communities than in the urban ones as their connection to the land and its many associated vagaries – worry about insects, weather, crop failure, etc – meant they still had a great use for their more traditional ceremonies, rituals and prayers, which were slowly becoming more of a mix of superstition and religion as the Church dominated society more and more. Perhaps the villagers saw the blended use of both ecclesiastical and pagan rituals as ‘hedging their bets’, as their good fortune was too vital to be leaving any aspect to chance. Aspects of the ecclesiastical ritual and belief were taken and used by villagers without hesitation. ‘An early eleventh-century ritual for blessing a field used the Pater noster prayer as a magic incantation.’32 During the early fifteenth century, a man by the name of John Smith, of Sleaford in Lincolnshire, England publicly claimed that ‘one was allowed to do conjurations and the casting of lots, not least because it had worked for St. Peter and St. Paul’.33 This sort of ‘logic’ must have been difficult for the Church to surmount, if it was to change the villagers’ view of what was acceptable and what was not, and there would have been many more incidents similar to the above for people to think they made a good argument for the continuation of their everyday practices. In fact, ‘there was a willingness to supply the instrumental aid the peasantry required through liturgical means, in order to establish the power of Christian rituals and relics’34 during the early Middle Ages. This sort of take-over by integration and then domination appeared to be a long-term strategy the Church had used for centuries, starting from its earliest moves to convert ‘pagans’ to the Christian faith across Europe and beyond. One historian claimed that “medieval Christianity ‘camouflaged’ pagan folk beliefs more than it suppressed them”35 and cited the example of a French friar observing women ‘sweeping the nearest chapel in their village, and then collecting the dust and throwing it into the air, hoping by this means to procure a favourable wind for their husbands or sons at sea’.36 Other historians have also given examples of how both village peasants and clergymen had utilised available ‘powerful forces’ and blended both Christian and pagan rituals for use in their everyday rural lives. Whether the clergymen, or the villagers, saw any distinction between the two forces is unclear, but struggling with everyday issues meant that, for the villagers at least, using all means available was better than possible disaster; and perhaps for the local clergy, being part of the rituals was better than being at odds with their fellow villagers, and avoiding any possible resentment or resistance to the ideas touted by the Church.

a rogation in Milan, against the plague, 16th century; by Giovan Mauro della Rovere

image source

Rituals like the yearly festivals - such as litanies and Rogations - celebrated in the rural communities, were extremely important to the villagers because they called on the aid and blessing of Church saints to protect them against natural catastrophes and plagues, and to ensure good harvests and fertile animals. These annual ceremonies could very well be labelled superstitious, as they would have been something carried out each year to ward off ‘bad luck’ against the important elements of village life. An English litany dated circa 1420 lists no fewer than sixty three saints, as well as God, Christ and the Holy Virgin.37 The practices ‘verged on the folklori[s]ation of religious ritual’38 and could easily be interpreted as ‘pagan’ if not for the calling on Church-sanctioned saints rather than pagan gods to bring ‘good luck’ to the community, and that each piece of symbolism used in the ceremonies was carefully given ecclesiastical meaning, firmly denying any form of pagan or folkloric residue. One interesting supposition put forward was that the Church ‘admitted by implication the power of pagan charms and amulets’,39 in that by their very attitude towards objects, rituals and anything else they deemed unchristian, they were giving credence to the idea that these things had some power that must be overcome or destroyed. As well as taking over pagan sites, then, the Church took over objects too, such as a Roman agate cameo from the first century A.D which showed a ‘laurel-crowned Jupiter holding a thunderbolt and leaning upon a lance, while the eagle is at his feet’40 but by the time Charles V gifted it to the Cathedral of Chartres in 1367 the image had been labelled as that of St. John the Evangelist with all the ecclesiastical ‘magic’ that implied. ‘A pagan image could thus assume a new power as a magical charm by means, not in spite of, its Christian adaptation.’41 If, by chance, such an object was taken through a rural village, and perhaps displayed for the villagers, they would not have been aware of any prior pagan claim to such an object, but would have believed whatever they were told about its – solely - religious power from the clergy.

Pope Gregory VII

image source

It wasn’t only villagers or local clerics who came under scrutiny over ‘pagan’ practices. During a meeting of the Council of Brixen, in 1080 A.D., Pope Gregory VII was charged with necromancy and conjuring, with a trusted servant testifying how he had opened a book of Gregory’s, ‘only to be confronted by a “multitude of dyuelles” ready to do their master’s bidding’,42 and later his so-called miracles which supported his canonisation were attributed to his use of diabolical magic; and he wasn’t the only pope accused of using such magic – the names of Pope’s Silvester and Benedict IX, along with Gregory VII appeared on a list of ‘papal and clerical necromancers’ created by John Bale. This association stayed with Gregory even up to the late sixteenth century, where it seems to have turned into a legend, such as how he was ‘able to send sparks of flame from the sleeves of this cloak’.43 If someone as powerfully religious a figure as a pope – especially one who was later made a saint - could be accused of working with diabolical forces and using magic, then it seems that the lines defining the differences between what was seen as religion as opposed to paganism were not so easy to distinguish. A surviving manuscript from a medieval friar blurs the distinction even more, as it explains ‘how to see ye spirites of ye aier’ and how to ‘constrayne any sp[i]rit to answer you and fulfil your entente’.44 Laypeople had often turned to clerics when seeking all manner of ways and means of getting through the rigours and perils of their everyday lives.

"May Pole by Hans Sebald Beham, woodcut, 1534, 1500-1550 No. 76 Meldemann"

image source

It appears that during the era encompassing the thirteenth to the sixteenth century in rural Medieval Europe, religion was predominantly interlaced with aspects which could have been defined as having pagan, magical or superstitious tones. It was a period where the Church was trying to establish a dominancy over traditional customs, and had some success merely by overlaying ecclesiastical meaning on a pagan ritual or object. Rural village life was likely more concerned with the practical everyday physical aspects of their community, but were not shy in utilising the more spiritual aspects available to them, coming up with distinctive blends of the two. It was not only the lay people using these tools, but clerics were not above using them either, which in itself lends a ‘blurred line’ aspect to the definition of appropriateness. Anyone either using or judging those customs would have been able to find or conclude whatever they wished, as to whether it was ‘safely’ religious or whether there was a more sinister, harmful or demonic factor involved, but basically it still simply came down to the matter of expediency and perception on the part of the viewer.

This essay was one I wrote as an assignment, while obtaining my University degree. I have included the reference list and bibliography - reference materials I used while writing - just as I’d had to for its submission. It has never before been published anywhere public, though. Images have been added for visual interest.

References

1 Gorski, Philip S. "Historicizing the Secularization Debate: Church, State, and Society in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, Ca. 1300 to 1700." American Sociological Review 65.1, Looking Forward, Looking Back: Continuity and Change at the Turn of the Millenium (2000) pp. 138.

2 "Pagan". Oxford Dictionaries. 6 October 2011. http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/pagan.

3 "Magic". Oxford Dictionaries. 6 October 2011. http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/magic.

4 "Superstition". Oxford Dictionaries. 6 October 2011. http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/superstition.

5 Kieckhefer, Richard. Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000, pp. 36.

6 ibid., pp. 36.

7 Schmitt, J-C. The Holy Greyhound: Guinefort, Healer of Children since the Thirteenth Century. 1979. Cambridge: np, 1983, pp. 15.

8 Kahane, Henry and Renee Kahane. "Christian and Un-Christian Etymologies." The Harvard Theological Review 57.1 (1964) pp. 33.

9 Kieckhefer, Richard. "The Specific Rationality of Medieval Magic." The American Historical Review 99.3 (1994) pp. 816.

10 ibid., pp. 816.

11 ibid., pp. 819.

12 ibid., pp. 828.

13 Mentzer, Raymond A. "The Persistence of "Superstition and Idolatry" among Rural French Calvinists." Church History 65.2 (1996) pp. 225.

14 ibid., pp. 225.

15 Bailey, Michael David. Magic and Superstition in Europe : A Concise History from Antiquity to the Present. Critical Issues in History. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, pp. 90.

16 ibid., pp. 126.

17 Scribner, R. W. Ritual and Popular Religion in Catholic Germany at the Time of the Reformation. Popular Culture and Popular Movements in Reformation Germany. London: np, 1987, pp. 41.

18 Kieckhefer, Richard. Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000, pp. 37.

19 Flint, Valerie I. J. The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe. Oxford: Clarendon, 1991, pp. 204.

20 Arnold, John. Belief and Unbelief in Medieval Europe. London

New York: Hodder Arnold, 2005, pp. 99.

21 Flint, Valerie I. J. The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe. Oxford: Clarendon, 1991, pp. 207.

22 ibid., pp. 207.

23 Kieckhefer, Richard. Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000, pp. 44.

24 ibid., pp. 45.

25 Bailey, Michael David. Magic and Superstition in Europe : A Concise History from Antiquity to the Present. Critical Issues in History. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, pp. 80.

26 Kieckhefer, Richard. Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000, pp. 58.

27 Lerner, Robert E. "Medieval Prophesy and Religious Dissent." Past & Present 72.Aug. (1976) pp. 9.

28 ibid., pp. 9.

29 Bailey, Michael David. Magic and Superstition in Europe : A Concise History from Antiquity to the Present. Critical Issues in History. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, pp. 80.

30 Shinners, John Raymond, ed. Medieval Popular Religion, 1000-1500 : A Reader. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 1997, pp. 286.

31 Part of ‘A ritual against intemperate weather from an early eleventh-century manuscript from Freising’.

Shinners, John Raymond, ed. Medieval Popular Religion, 1000-1500 : A Reader. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 1997, pp. 259.

32 Arnold, John. Belief and Unbelief in Medieval Europe. London

New York: Hodder Arnold, 2005, pp. 96.

33 ibid., pp. 96.

34 ibid., pp. 97.

35 Gorski, Philip S. "Historicizing the Secularization Debate: Church, State, and Society in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, Ca. 1300 to 1700." American Sociological Review 65.1, Looking Forward, Looking Back: Continuity and Change at the Turn of the Millenium (2000) pp. 144.

36 ibid., pp. 144.

37 Shinners, John Raymond, ed. Medieval Popular Religion, 1000-1500 : A Reader. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 1997, pp. 270-273.

38 Vauchez, A. Liturgy and Folk Culture in the Golden Legend. Trans. Scheider, Margery J. The Laity in the Middle Ages. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1993, pp. 138.

39 Heckscher, W. S. "Relics of Pagan Antiquity in Medieval Settings." Journal of the Warburg Institute 1.3 (1938) pp. 215.

40 ibid., pp. 216.

41 ibid., pp. 216.

42 Parish, Helen L. Monks, Miracles and Magic: Reformation Representations of the Medieval Church. np: Routledge, 2005, pp. 136.

43 ibid., pp. 137.

44 ibid., pp. 141.

(extra tags: #religion #pagan #superstition #culture #medieval #magic)