Warning:

this post does not contain any dating advice but rather a number of possible scenarios that people may encounter whilst on a date. The post offers an analysis of these scenarios as well as the economic concepts supporting this analysis. I hope you enjoy the post.

Economics can be applied to so many areas. In previous posts I have looked at a work day and a trip to the supermarket. In this post I will look at how economics can be applied to going on a date. The first question could be ‘where to go on the date?’

If it is a first date, there is a good chance that the person asking has a location and activity planned. The person being asked will most likely answer in the affirmative if the date meets their conditions. Such conditions may include absence of existing relationship, availability on the date of the proposed date, and the attractiveness of the person proposing the date.

Once on the date, decisions need to be made around conversation topics. For example, should the focus be on finding out more about the other person or should the focus be about impressing the other person. This really depends on the objective of the date. Is the objective of the date to get a second date? This would imply that the person you are on the date with is desirable and possibly in your current opinion second date worthy. Trying to impress the other person is a strategy that might be adopted. This strategy could work and make a person appear more appealing or it could make them appear boring or self-obsessed.

If the objective is determine if the other person is worth going out with on a second date. The strategy might be to find out as much as possible about the other person. This could be useful for finding out more about the other person if that person is open and willing to share information about themselves. The other person may not be completely honest and might just be trying to impress. It is also possible the other person could be offended if it appears that they are being interrogated. Another strategy might involve discovering mutual interests and building conversations around these mutual interests. This could build trust and a rapport. This could also backfire if conflicting points of view emerge regarding a particular topic.

The next decision may involve who pays. In many countries it is customary for the male to pay if he initiated the date. If the male did not initiate the date, the male may still pay or the bill could be split. Some females expect the male to pay while others are insulted. The male needs to gauge beforehand if paying the full bill is the best strategy based on what he knows and discovered about the female from the date and before the date.

The next decision may involve deciding if the date should be extended and if so what next and if not how will each person return home. Let’s assume the date ends as expected. Do they return home using the same mode of transport as they arrived? If both travelled by car then that would seem obvious. If they arrived using public transport or taxi, they could travel together or separately. The decision could depend on culture or individual’s own practice. As it is a first date it might be difficult to know what is expected. A more conservative approach of immediately going separate ways after the date might be adopted. If the date went well this approach might seem cold and damage chances of future dates.

Let’s take a look at dates after the couple have got to know each other better. Let’s say we are now up to the twentieth date. The question of where to go might become a more relevant decision. Date activities and places are more likely to be decided on a more mutual basis. Do the couple value the same activities, places, and locations equally? There is a high chance they have different preferences and will favour different activities and locations. How should they decide where to go and what to do? How often should each person get to do the activity they prefer? What are the consequences of one person consistently getting their own way? What are the consequences of one person strongly disliking the other person’s preferences? Economics can be used to add some perspective on these questions. This will be explained in the second part of this post.

How about the other first date decisions? Are they still relevant on later dates? This probably depends on the individual couples. Conversations should flow more naturally. There should be less pressure to impress the other person and less need to understand more about the other person. If things are going well, more focus should be just on enjoying the moment. If things are going badly, more focus could be spent on resolving situations and finding common ground or more effort may go into proving the other person is wrong. The scenario where things are going badly is probably more interesting from both a psychology perspective and an economics perspective. It comes down to what a person is trying to achieve? Is what that person trying to achieve actually in their own and the other person’s best interest? What strategy is being applied to achieve these objectives? Is the person actively making decisions or are they acting more instinctively?

After running through some of the possible scenarios a person may encounter on a date, let’s take a look at some of the economic concepts that can be applied to explain how a person could use economics to reach a decisions in the above scenarios.

Economic Concept 1: Game Theory – Battle of the Sexes

Game theory is one of my favourite areas in economics. The three games of prisoners dilemma, chicken game, and battle of sexes are often cited as the three core games in game theory. This post will focus on battle of sexes. What is the battle of the sexes game? It is fundamentally explained as a couple deciding on what to do or where to go on a date. The game is generally presented as the choice between two options. One option is preferred by the male and the other option is preferred by the female. The game is presented in a matrix.

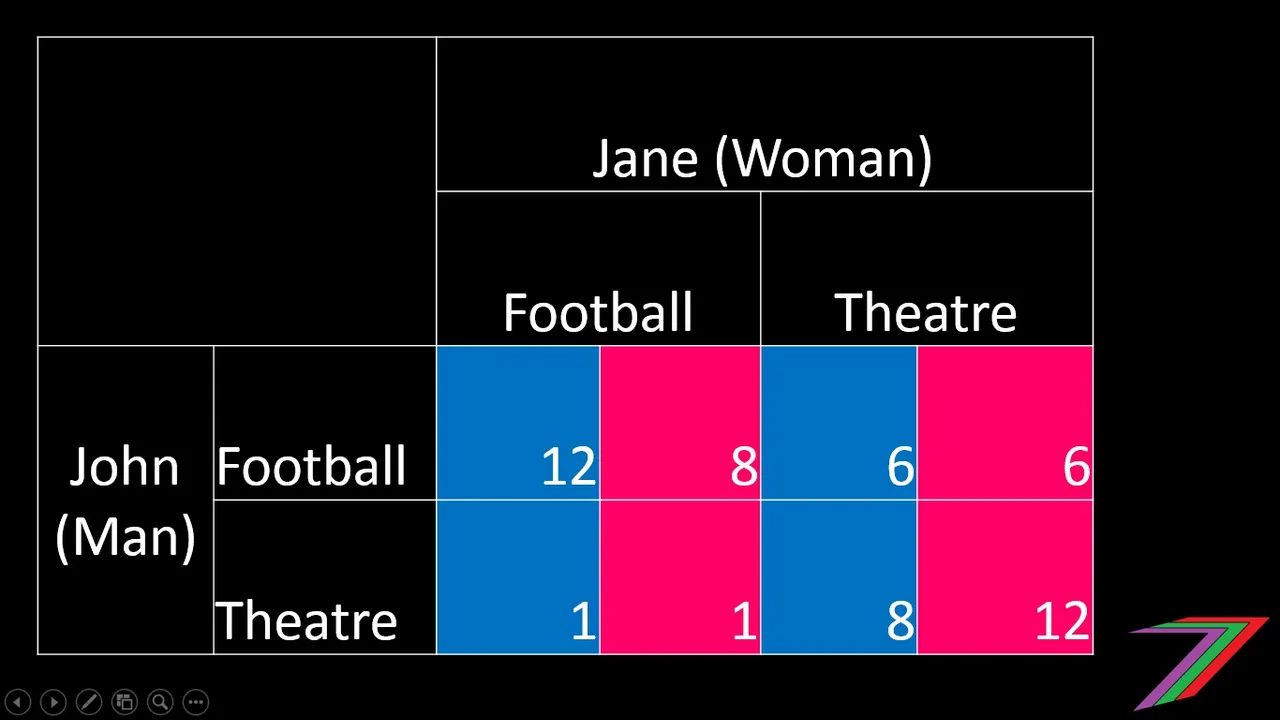

Battle of the Sexes Matrix

In the battle of the sexes matrix expressed in the example above, I have used two stereotypical male and female activities to explain the battle of the sexes game. The male (John) enjoys going to the football more than going to the theatre and the female (Jane) enjoys going to the theatre more than going to the football. In the game presented in the matrix, there are four possible outcomes. They are as follows:

- Both go to the football

- Both go to the theatre

- John goes to the football and Jane goes to the theatre

- Jane goes to the football and John goes to the theatre

For each outcome a value has been assigned (payout). The blue squares represent the payouts to John and the pink squares represent the payouts to Jane from each outcome. The payouts represent the amount of enjoyment or satisfaction each person receives from an outcome. If they both go to the football, John will receive a payout of 12 and Jane a payout of 8. If they both go to the theatre, John will receive a payout of 8 and Jane a payout of 12.

If we assume Jane and John communicate, the option of Jane going to the football and John going to the theatre should be ruled out as neither are selecting their preferred option. This leaves us with John compromising and going to the theatre with Jane, Jane compromising and going to the football with John, or neither compromising with Jane going to the theatre by herself and John going to the football by himself. From the game displayed in the matrix, John and Jane will either go to the football or the theatre together rather than go to their preferred activity alone. The question remains how often do the couple go with John’s preferred option and often do they go with Jane’s preferred option? The ‘Nash mixed equilibrium’ can be calculated to approximate this selection, this is not covered in this post due to the mathematical complexity of the calculation.

Economic Concept 2: Game theory – Repeat the Game

So we have taken a quick look at the basic theory behind the battle of sexes game. The battle of the sexes game is generally viewed, for simplicity, as a one-off game (no second date). ‘Repeat the game’ analysis looks at maximising the long-run return. Repeated games can have a known finite number of games or an unknown finite number of games, or an infinite number of games. The strategies vary depending on the type of repeated game. Repeated games with known finite number of games are easier to plan for as the players just need to work backwards. Other strategies that players can use for repeated games are the ‘Nash mixed equilibrium’, ‘tit for tat’ and the ‘Davies mixed equilibrium’ strategies. This post will not go into the details of these strategies.

Games or variations of games are generally repeated. Dating should be a repeat game if all goes well. In regards to selection of activities and location of date, it might be wise to allow some alternation in selection. If one person dominates selection, it is possible that the opinion of the dominant selector in the eyes of the less dominant selector will fall, hence the possibility of a reduction in future dates (possible break up).

Economic Concept 3: Imperfect information

Imperfect information is almost universal to any decision making. For first dates in particular, there is generally limited information to base decisions on; even with information from social media there are so many things we do not know about a person. People need to decide how much research should be undertaken prior to the date. Is it worth digging through all the person’s social media sites, googling them (use of internet search engines) or doing background checks on them? Does the effort put in equal the reward at the end?

Economic Concept 4: Risk

There are many ways of looking at risk. It can be a qualitative approach of identifying and describing risk or it could be a quantitative approach of assigning costs and probabilities of occurrence. It is highly unlikely anyone would apply a technical quantitative analysis of the risks of making the wrong move on a date. A quick qualitative analysis on the other hand is quite possible. This analysis can be made easier with the use of social media such as Facebook. The person’s Facebook page could provide an indication of the person’s like and dislikes and help with conversation topics. The overuse of such material could also make the person appear like a stalker. It is all about managing the possible risks and being aware of the possible pitfalls. There is even a risk of over thinking and over preparing which could disrupt the flow of the date.

Behavioural Economics

Behavioural economics is another economics area that can be discussed regarding dating. Behavioural economics would be of interest to those studying dating behaviour and useful for those trying to understand why people behaviour in such a way and their level of success. Behavioural economics will not be discussed in this post. This would be more relevant to a research paper or post. This post is merely using examples of dating scenarios that can be analysed using economics.

This takes me to the end of this post. I hope you enjoyed it. I will post more blogs relating to ‘Economics is Everywhere’ in the weeks to come. Thank you for reading.